Orwell's Animal Farm Crack

Halas & Batchelor studio's classic and controversial animation of Animal Farm was the first ever British animated feature film. This landmark illustrated edition of Orwell’s novel was first published alongside it and features the original line drawings by the film's animators, Joy Batchelor and John Halas, some of which feature in this extract. George Orwell's Animal Farm is an example of a political satire that was intended to have a 'wider application,' according to Orwell himself, in terms of its relevance. Stylistically, the work shares many similarities with some of Orwell's other works, most notably 1984.

By Dr Oliver Tearle

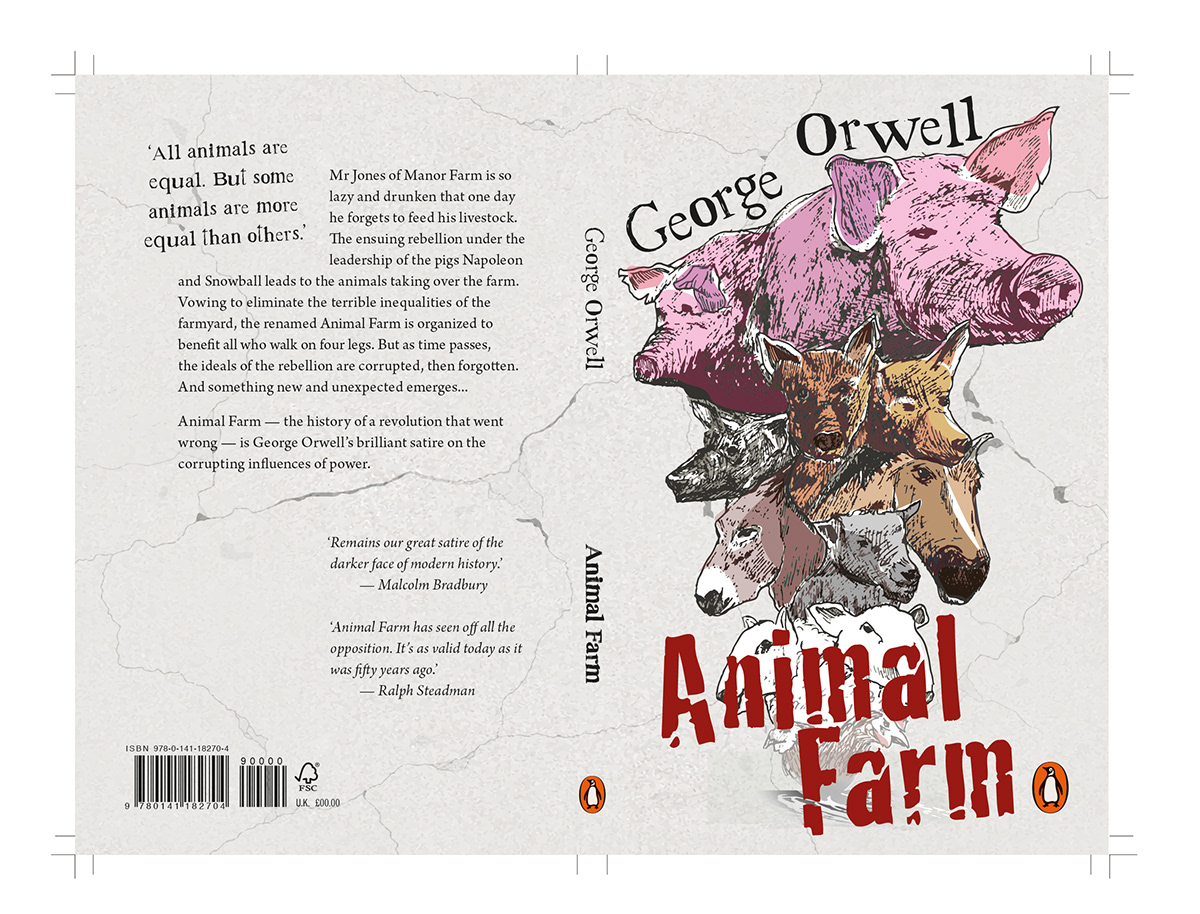

Animal Farm is, after Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell’s most famous book. Published in 1945, the novella (at under 100 pages, it’s too short to be called a full-blown ‘novel’) tells the story of how a group of animals on a farm overthrow the farmer who puts them to work, and set up an equal society where all animals work and share the fruits of their labours. However, as time goes on, it becomes clear that the society the animals have constructed is not equal at all. It’s well-known that the novella is an allegory for Communist Russia under Josef Stalin, who was leader of the Soviet Union when Orwell wrote the book. Before we dig deeper into the context and meaning of Animal Farm with some words of analysis, it might be worth refreshing our memories with a brief summary of the novella’s plot.

Animal Farm: plot summary

The novel opens with an old pig, named Major, addressing his fellow animals on Manor Farm. Major criticises Mr Jones, the farmer who owns Manor Farm, because he controls the animals, takes their produce (the hens’ eggs, the cows’ milk), but gives them little in return. Major tells the other animals that man, who walks on two feet unlike the animals who walk on four, is their enemy. They sing a rousing song in favour of animals, ‘Beasts of England’. Old Major dies a few days later, but the other animals have been inspired by his message.

Two pigs in particular, Snowball and Napoleon, rouse the other animals to take action against Mr Jones and seize the farm for themselves. They draw up seven commandments which all animals should abide by: among other things, these commandments forbid an animal to kill another animal, and include the mantra ‘four legs good, two legs bad’, because animals (who walk on four legs) are their friends while their two-legged human overlords are evil.

The animals lead a rebellion against Mr Jones, whom they drive from the farm. They rename Manor Farm ‘Animal Farm’, and set about running things themselves, along the lines laid out in their seven commandments, where every animal is equal. But before long, it becomes clear that the pigs – especially Napoleon and Snowball – consider themselves special, requiring special treatment, as the leaders of the animals. Nevertheless, when Mr Jones and some of the other farmers lead a raid to try to reclaim the farm, the animals work together to defend the farm and see off the men. A young farmhand is knocked unconscious, and initially feared dead.

Things begin to fall apart: Napoleon’s windmill, which he has instructed the animals to build, is vandalised and he accuses Snowball of sabotaging it. Snowball is banished from the farm. During winter, many of the animals are on the brink of starvation. Napoleon engineers it so that when Mr Whymper, a man from a neighbouring farm with whom the pigs have started to trade (so the animals can acquire the materials they need to build the windmill), visits the farm, he overhears the animals giving a positive account of life on Animal Farm.

Without consulting the hens first, Napoleon organises a deal with Mr Whymper which involves giving him many of the hens’ eggs. They rebel against him, but he starves them into submission, although not before nine hens have died. Napoleon then announces that Snowball has been visiting the farm at night and destroying things.

Napoleon also claims that Snowball has been in league with Mr Jones all the time, and that even at the Battle of the Cowshed (as the animals are now referring to the farmers’ unsuccessful raid on the farm) Snowball was trying to sabotage the fight so that Jones won. The animals are sceptical about this, because they all saw Snowball bravely fighting alongside them. Napoleon declares he has discovered ‘secret documents’ which prove Snowball was in league with their enemy.

Life on Animal Farm becomes harder for the animals, and Boxer, while labouring hard to complete the windmill, falls and injures his lung. The pigs arrange for him to be taken away and treated, but when the van arrives and takes him away, they realise too late that the van belongs to a man who slaughters horses, and that Napoleon has arranged for Boxer to be taken away to the knacker’s yard and killed.

Squealer lies to the animals, though, and when he announces Boxer’s death two days later, he pretends that the van had been bought by a veterinary surgeon who hadn’t yet painted over the old sign on the side of the van. The pigs take to wearing green ribbons and order in another crate of whisky for them to drink; they don’t share this with the other animals.

A few years pass, and some of the animals die, Napoleon and Squealer get fatter, and none of the animals is allowed to retire, as previously promised. The farm gets bigger and richer, but the luxuries the animals had been promised never materialised: they are told that the real pleasure is derived from hard work and frugal living. Then, one day, the animals see Squealer up on his hind legs, walking on two legs like a human instead of on four like an animal.

The other pigs follow; and Clover and Benjamin discover that the seven commandments written on the barn wall have been rubbed off, to be replace by one single commandment: ‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.’ The pigs start installing radio and a telephone in the farmhouse, and subscribe to newspapers.

Finally, the pigs invite humans into the farm to drink with them, and announce a new partnership between the pigs and humans. Napoleon announces to his human guests that the name of the farm is reverting from Animal Farm to the original name, Manor Farm. The other animals from the farm, observing this through the window, can no longer tell which are the pigs and which are the men, because Napoleon and the other pigs are behaving so much like men now.

Things have gone full circle: the pigs are no different from Mr Jones (indeed, are worse).

Animal Farm: analysis

First, a very brief history lesson, by way of context for Animal Farm. In 1917, the Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II, was overthrown by Communist revolutionaries. These revolutionaries replaced the aristocratic rule which had been a feature of Russian society for centuries with a new political system: Communism, whereby everyone was equal. Everyone works, but everyone benefits equally from the results of that work. Josef Stalin became leader of Communist Russia, or the Soviet Union, in the early 1920s.

However, it soon became apparent that Stalin’s Communist regime wasn’t working: huge swathes of the population were working hard, but didn’t have enough food to survive. They were starving to death. But Stalin and his politicians, who themselves were well-off, did nothing to combat this problem, and indeed actively contributed to it. But they told the people that things were much better since the Russian Revolution and the overthrow of the Tsar, than things had been before, under Nicholas II. The parallels with Orwell’s Animal Farm are crystal-clear.

Animal Farm is an allegory for the Russian Revolution and the formation of a Communist regime in Russia (as the Soviet Union). We offer a fuller definition of allegory in a separate post, but the key thing is that, although it was subtitled A Fairy Story, Orwell’s novella is far from being a straightforward tale for children. It’s also political allegory, and even satire. The cleverness of Orwell’s approach is that he manages to infuse his story with this political meaning while also telling an engaging tale about greed, corruption, and ‘society’ in a more general sense.

One of the commonest techniques used in both Stalinist Russia and in Animal Farm is what’s known as ‘gaslighting’ (meaning to manipulate someone by psychological means so they begin to doubt their own sanity; the term is derived from the film adaptation of Gaslight, a play by Patrick Hamilton). For instance, when Napoleon and the other pigs take to eating their meals and sleeping in the beds in the house at Animal Farm, Clover is convinced this goes against one of the seven commandments the animals drew up at the beginning of their revolution.

But one of the pigs has altered the commandment (‘No animal shall sleep in a bed’), adding the words ‘with sheets’ to the end of it. Napoleon and the other pigs have rewritten history, but they then convince Clover that she is the one who is mistaken, and that she’s misremembered what the wording of the commandment was.

Another example of this technique – which is a prominent feature of many totalitarian regimes, namely keep the masses ignorant as they’re easier to manipulate that way – is when Napoleon claims that Snowball has been in league with Mr Jones all along. When the animals question this, based on all of the evidence to the contrary, Napoleon and Squealer declare they have ‘secret documents’ which prove it. But the other animals can’t read them, so they have to take his word for it. Squealer’s lie about the van that comes to take Boxer away (he claims it’s going to the vet, but it’s clear that Boxer is really being taken away to be slaughtered) is another such example.

Much as Stalin did in Communist Russia, Napoleon actively rewrites history, and manages to convince the animals that certain things never happened or that they are mistaken about something. This is a feature that has become more and more prominent in political society, even in non-totalitarian ones: witness our modern era of ‘fake news’ and media spin where it becomes difficult to ascertain what is true any more.

The pigs also convince the other animals that they deserve to eat the apples themselves because they work so hard to keep things running, and that they will have an extra hour in bed in the mornings. In other words, they begin to become the very thing they sought to overthrow: they become like man.

They also undo the mantra that ‘all animals are equal’, since the pigs clearly think they’re not like the other animals and deserve special treatment. Whenever the other animals question them, one question always succeeds in putting an end to further questioning: do they want to see Jones back running the farm? As the obvious answer is ‘no’, the pigs continue to get away with doing what they want.

Squealer is Napoleon’s propagandist, ensuring that the decisions Napoleon makes are ‘spun’ so that the other animals will accept them and carry on working hard.

And we can draw a pretty clear line between many of the major characters in Animal Farm and key figures of the Russian Revolution and Stalinist Russia. Napoleon, the leader of the animals, is Joseph Stalin; Old Major, whose speech rouses the animals to revolution, represents Vladimir Lenin, who spearheaded the Russian Revolution of 1917; Snowball, who falls out with Napoleon and is banished from the farm, represents Leon Trotsky, who was involved in the Revolution but later went to live in exile in Mexico. Squealer is based on Molotov (after whom the Molotov cocktail was named); Molotov was Stalin’s protégé, much as Squealer is encouraged by Napoleon to serve as Napoleon’s right-hand (or right-hoof?) man (pig).

Animal Farm very nearly didn’t make it into print at all. First, not long after Orwell completed the first draft in February 1944, his flat on Mortimer Crescent in London was bombed in June, and he feared the typescript had been destroyed. Orwell later found it in the rubble. Then, Orwell had difficulty finding a publisher. T. S. Eliot, at Faber and Faber, rejected it because he feared that it was the wrong sort of political message for the time (you can read Eliot’s letter to Orwell here). The novella was eventually published the following year, in 1945, and its relevance – as political satire, as animal fable, and as one of Orwell’s two great works of fiction – shows no signs of abating.

The author of this article, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others, The Secret Library: A Book-Lovers’ Journey Through Curiosities of History and The Great War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.

Image: via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s been 75 years since the comrades of the once (and future) Manor Farm first took up the anthem “Beasts of England” and surprised themselves by routing out the tyrant farmer, Mr. Jones, from his holdings. Seventy-five years since the seemingly inalterable tenets of Animalism were scrawled in white paint on the side of the barn, and the enthusiastic dreamer Snowball strove for his short-lived utopia before running afoul of the Berkshire boar Napoleon’s autocratic ambitions.

In the decades since the publication of George Orwell’s seminal work of anti-Stalinist satire, we have seen the collapse of the regime that disturbed and inspired its author; the beginning and end of the Cold War, with all its attendant horrors; and the rise and fall of any number of would-be Napoleons, both at home and abroad. Animal Farm, once a work so controversial that it seemed unlikely to find a publisher, has served for so long, and in so many school curriculums, as the predominant introduction to the concept of totalitarianism that it is in danger of being perceived as trite.

With Animal Farm, Orwell—then a 42-year-old democratic socialist known primarily for essays and journalism exploring social injustice and class iniquities across Europe—hoped only to dissuade his countrymen from what he recognized as a dangerous infatuation with Joseph Stalin. It is indisputable that an author’s intentions for his or her work usually don’t survive publication, let alone the author’s death. Nothing of Animal Farm’s success during Orwell’s lifetime could really augur the varied purposes it would come to serve, or the global behemoth it would quickly become. Cultist simulator download for mac. Pushing back on a critique that Orwell was too light-handed in his reproach of totalitarianism, Julian Symons wrote, “In a hundred years’ time perhaps, Animal Farm may be simply a fairy story, today it is a political satire with a good deal of point.”

That was then, and this is now. Luckily, having spent the last seven and a half decades heeding its warnings and taking its lessons to heart, we have pulled ahead of the dangers Animal Farm hinted we might one day face. As a species, we have defied Orwell’s wildest expectations. Wouldn’t he be thrilled to know that we no longer have need of a text that so explicitly decries authoritarianism, fearmongering, tribalism, historical erasure, factual manipulation and war as an engine of national pride?

Reader, I jest. All evidence points to the fact that we’re in a great deal of very familiar trouble the whole world over. That we so dependably manage to be, despite the existence of prophetic works like Animal Farm, should worry us to the point of despair. But this is the way of our species: memory fades. We grow bored with the lessons of the past. We tell ourselves: things could never get as bad as they once were because, unlike those who came before us, we are good people who know better than to let it happen again.

How, then, are we to read Animal Farm circa 2020?

I was raised in the former Yugoslavia in the mid-1980s, in a household and culture gripped by the distinction between “indoor” and “outdoor” talk. Understanding this was as essential to my early upbringing as table manners or the correct protocol for crossing the street. The gist was: certain conversations were appropriate for public consumption, while others belonged only within the confines of the house. You were expected to use your common sense to distinguish between the two as you grew older, but your starting point was to assume that anything overheard at the dinner table qualified as indoor talk and was not to be discussed with people outside the home; that is, outdoors. You think I’m talking about politics here, reader, but I’m not. Politics was so out of bounds that I can’t remember any adult ever declaring support for any candidate in my presence until we moved to America. I’m talking about simple details of daily existence: a new pencil case that might be misconstrued as a sign of increased wealth, or a sandwich that might give a nosy stranger on a train some false idea about the demographic composition of our family because one of its ingredients may or may not be a certain kind of ham.

People incapable of recognizing the distinction between indoor and outdoor talk—people who might volunteer, a little too eagerly, the outcome of some private development, or some holiday plan, or, the worst of all sins, the affairs of some mutual acquaintance—were to be regarded with disdain and suspicion. For if they didn’t value the sanctity of their own indoor talk, imagine the damage they could inflict if they somehow got ahold of yours!

I have been living in America for 23 years and still have a hair trigger where indoor talk is concerned. This will be with me forever, I suspect, probably hardwired in some remote twist of trauma-blitzed DNA inherent in people worn down by centuries of imperialism and political volatility. Perhaps that’s why, when I did eventually read Animal Farm—sometime in 1997, no doubt, in a suburb of Atlanta where my mother and I eventually wound up after spending most of the Yugoslav Wars in Cyprus and Egypt—the character with whom I felt the most kinship was Benjamin the Donkey. I was heartbroken by the heavily foreshadowed death of Boxer the horse, who seemed to stand for so much of what was good and true; but all I really cared about was whether his little donkey friend would successfully dodge a similar fate.

Animal Farm Orwell Pdf

Benjamin is Boxer’s closest companion. A cynic of uncertain age, he is known for having outlived all his peers by keeping steadfastly silent. Animal Farm scholars have often cast him as the allegorical stand-in for Russia’s disillusioned older generation, as wary of the Revolution as they were of the tsarist society it dismantled. And indeed, in his keep-it-close-to-the-vest reticence, I recognized many of my grandparents’ tendencies: an obsession with common sense; a potent distrust of propaganda; a tendency to eye roll at naïveté; and above all, a really keen sense of the difference between indoor and outdoor talk. Ricochet for mac.

Benjamin is a survivor. But his carefully maintained silence comes crashing down when his dear friend, Boxer, is carted off to Willingdon after succumbing to labor and age. Though Squealer persuades the other animals that Boxer is, of course, bound only for the animal hospital to receive care, Benjamin finally breaks with precedent to tell them the terrible truth he has always been literate enough to know: the van taking Boxer away bears the insignia of the dreaded knacker, and Boxer is going to his doom. With the death of what is arguably the book’s most beloved character, Orwell shows us the futility of Benjamin’s revelation. It is too late for fraternal duty to override self-preservation.

The notion that Western countries are clever and strong enough to both recognize and resist the grip of totalitarianism is a dangerous myth. A fairy story, if you will—one to which we are ironically susceptible, because being shaped by Animal Farm deludes us into thinking we are sufficiently armed. “We already know what we need to know,” we might say. “We all know that individuality is a form of resistance, and that anyone who hungrily pursues power is probably unworthy of attaining it.”

Here’s some formerly indoor talk: too many of us take our freedoms for granted. Even now, those of us who never grew up fearing the dangers of indoor talk are far too cozy in the belief that we are safe from the forces that could plunge us back into a world that demands it. Animal Farm asks us to work against that delusion. We are making great strides in this direction already. In opening up about the persistent, daily injustices that shape life—micro- and macroaggressions, racial profiling, police brutality, exploitation of body and mind, intolerance, erasure, assault, exclusion—even the most disenfranchised among us have found themselves wielding, if even for a moment, sudden and unprecedented power to enact change that once took a lifetime. At our best, we are able to stand with and for one another like never before. We celebrate one another’s rights to individuality, expression, faith and love.

Orwell's Animal Farm

We have a quarter century to test Julian Symons’ hopeful prediction, and usher Animal Farm into the niche of fairy stories. I am not sure even that is time enough. It’s entirely possible that we will never live in a world free of Napoleons and the Squealers who prop them up; that we will always find ourselves peering through windows, unable to tell the difference between the people who claim to be serving our interests and the enemies to whom they have betrayed us. But it’s also possible that we will never be isolated enough to keep signs of danger to ourselves as we once did; that we will openly decry every change to our commandments and insist on reiterating the history we know to be true, however terrible its contents. It is possible that we will recognize, without the blinders of Squealer’s “proper perspective,” that danger to one is danger to all; that we will read the knacker’s signage aloud, for all to hear, before it’s too late.

Animal Farm Orwell Movie

From ANIMAL FARMpublished by arrangement with Berkley/Signet Classics, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 1946, Harcourt Inc. Copyright © renewed 1977, Sonia Brownell Orwell. Introduction Copyright © 2020, Téa Obreht.